Microbial Cosmologies: A Way Of Improving Urban And Space Symbiotic Relationships Between Humans and Microbes?

“Life did not take over the world by combat, but by networking.”

Symbiotic relationships have shaped our planet and are among the interspecies relationships that drive biodiversity across ecosystems. Are you able to picture yourself in symbiotic harmony with microbes, such as bacteria and viruses, in your environment? Well, believe it or not, we are!

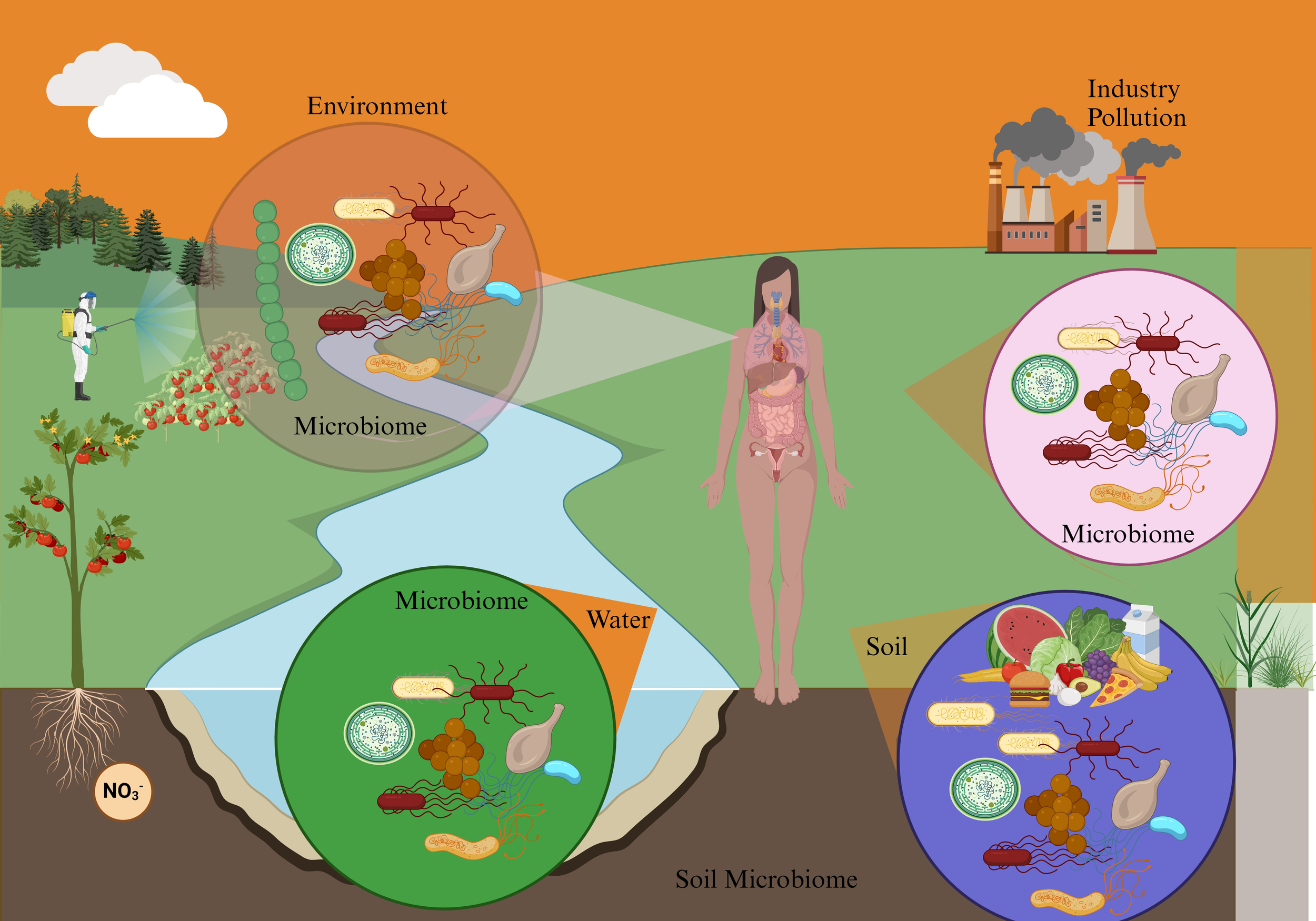

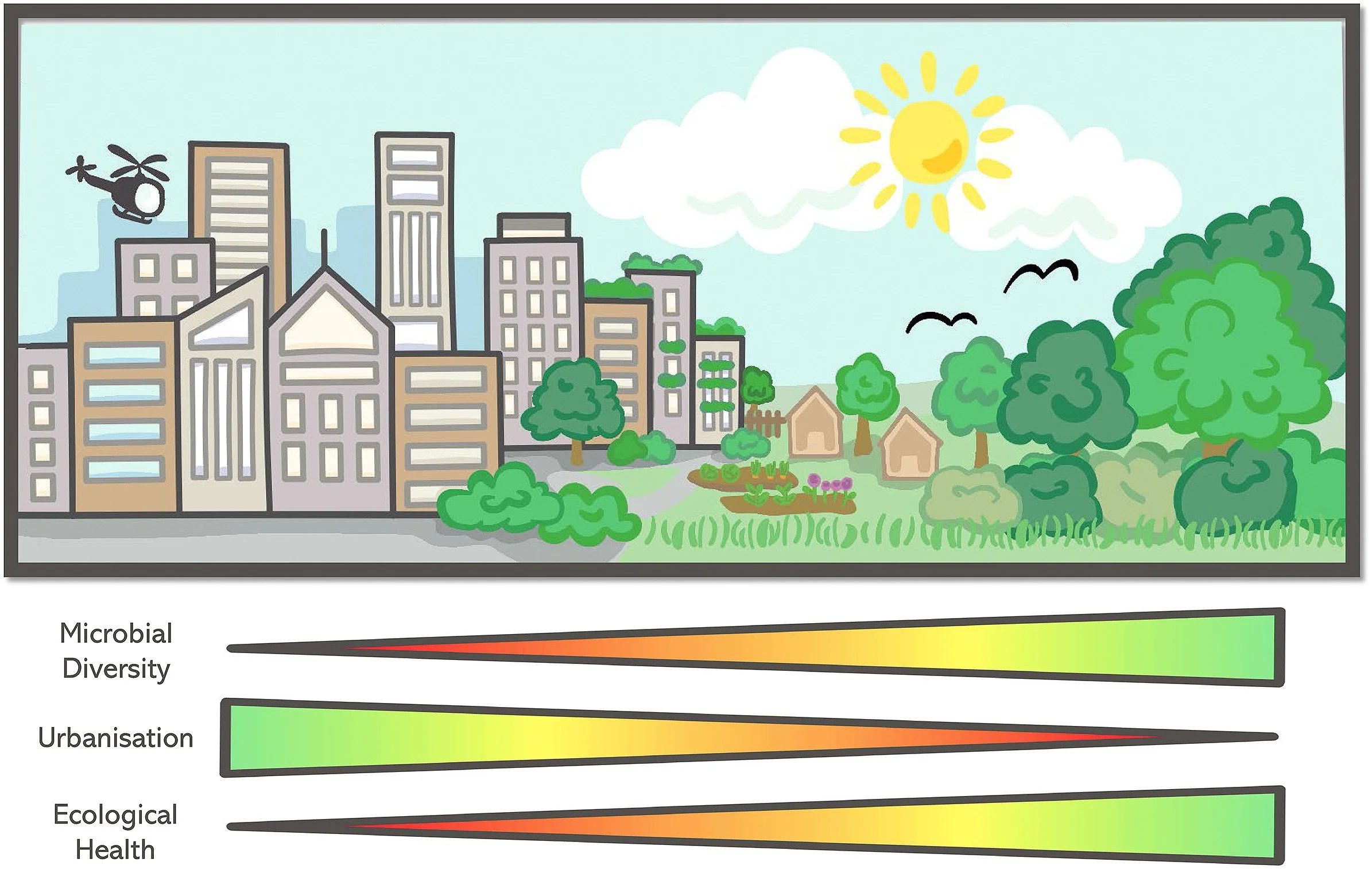

Humans have an ancestral, direct, and intimate relationship with the environment that spans approximately 2 million years. Our symbiotic relationships with microbes play critical roles in our well-being, making the human microbiome essential for our health. Yet this microbiome is acquired from our microbial environment, meaning that an “unhealthy microbial environment” or a “less diverse microbial environment” will have repercussions for our health. For example, urbanization has decreased our exposure to harmful pathogens, but there is growing evidence that these environmental health benefits might also be causing a hidden disease burden through immune dysregulation, as proposed also by the hygiene hypothesis.

Furthermore, recent research has shown that urbanization reshapes entire environmental microbiomes, since it has been observed that soil and phyllosphere microbial communities in city parks differ dramatically from those in minimally disturbed natural spaces, increasing the concern of maintaining healthy biodiverse urban landscapes, since natural ecosystems act as a bridge between the environmental microbiota and the human microbiome. However, novel concepts such as Microbial Cosmologies offer new avenues for addressing modern issues related to disrupted microbial communities in urban landscapes and their repercussions on the human microbiome, thereby influencing human health.

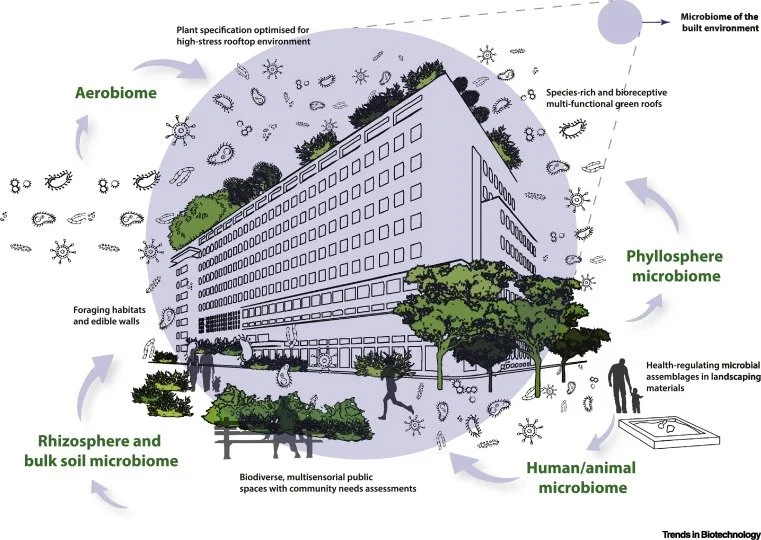

Microbiome-Inspired Green Infrastructure (MIGI) envisions ways of integrating microbial communities into full practices when designing urban landscapes. Integration of MIGI models offers ways to restore beneficial human–microbe interactions in urban landscapes, enhance ecosystem services, and support public health by designing green spaces that consider the microbiome from the start. Approaches based on MIGI aim to increase the selection of plants and soils that support diverse microbiomes, use bioreceptive materials that encourage beneficial microbial growth, inoculate landscaping materials with microbes to enhance ecological function, and create green spaces that foster natural microbe-human interactions. This novel approach also offers benefits to the key concept of microbial resilience in urban landscapes, since a decrease in microbial diversity impacts the ability of microbial communities to respond and recover from disturbances like pollution, climate change, or habitat degradation, and disrupts key functions like nutrient cycles, degradation of pollutants, green-space plant health, and maintenance of urban ecosystem functioning. For example, MIGI approaches can restore microbial functional redundancy, dispersal, repositories, and overall diversity, fostering potential healthy human-microbe interactions that ultimately stabilize urban human microbiomes and enhance human urban health.

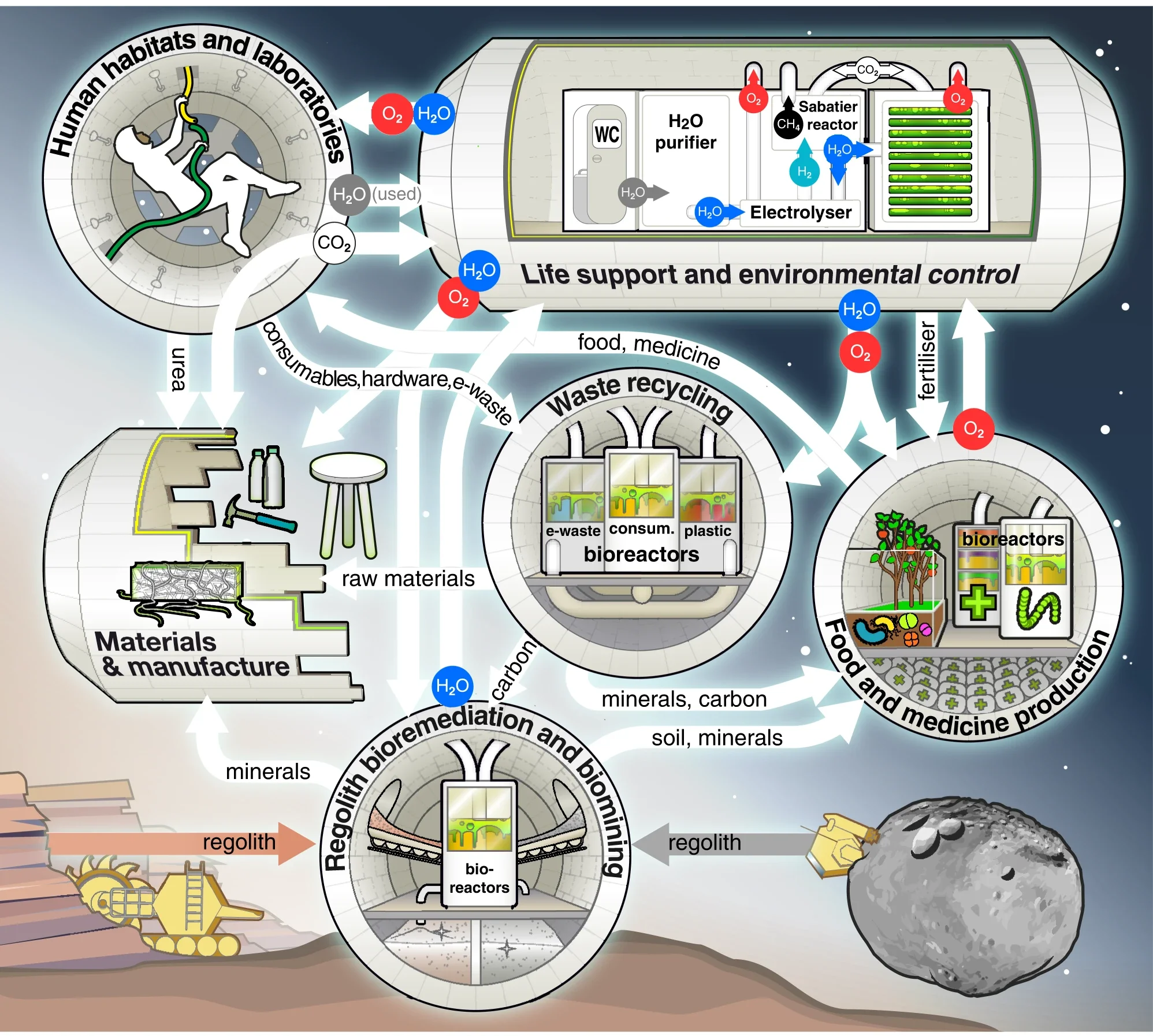

Not only Microbial Cosmologies can help restore and reshape our microbial urban landscapes, but they also open the door to designing entirely new human-microbe symbiotic habitats in extreme environments like outer space, since novel research has shown that microbes can sustain life-support systems, recycle waste, produce oxygen, and even manufacture building materials in space through processes such as microbial fuel cells, biomining, and myco-architecture. Overall, these ideas show that Microbial Cosmologies can transform not only our cities but also the future of human habitats. By creating microbial corridors—urban networks of biodiverse soils, plants, and bioreceptive materials—we can restore environmental microbiomes, improve human–microbe interactions, and develop healthier, more resilient urban ecosystems; and as space research shows, microbes are just as vital beyond Earth, capable of recycling waste, producing oxygen, and supporting habitat construction on the Moon or Mars. Referencing our opening quote, seeing microbes as our ancestral symbiotic partners rather than a source of disease will allow us to imagine a future in which human life on Earth or in space is supported by vibrant, symbiotic microbial worlds.

What are your thoughts on improving symbiotic relationships between microbes and humans? Can you think of any potential negative impacts from rapid microbial evolution and the potential acquisition of pathogenicity in the implementations of Microbial Comologies?

Leave your comment below!

Also, if you are looking to explore more about microbial and ecological corridors, the link below is a great place to start your journey.