Horizontal Gene Transfer: An Infinite Source of Bacterial Dark Matter

“When you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

Have you ever wondered where genetic diversity —the raw material for evolution— comes from in bacteria? Well, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is the key! As we know, bacteria reproduce asexually mostly through binary fission, producing daughter cells that are essentially genetically identical to the parent; however, HGT allows genetic diversity to be acquired and exchanged across unrelated lineages. For example, HGT allows bacteria to acquire foreign DNA from their environment, introducing new genes that can dramatically alter bacterial functions, reshape bacterial genomes, and set lineages on evolutionary pathways.

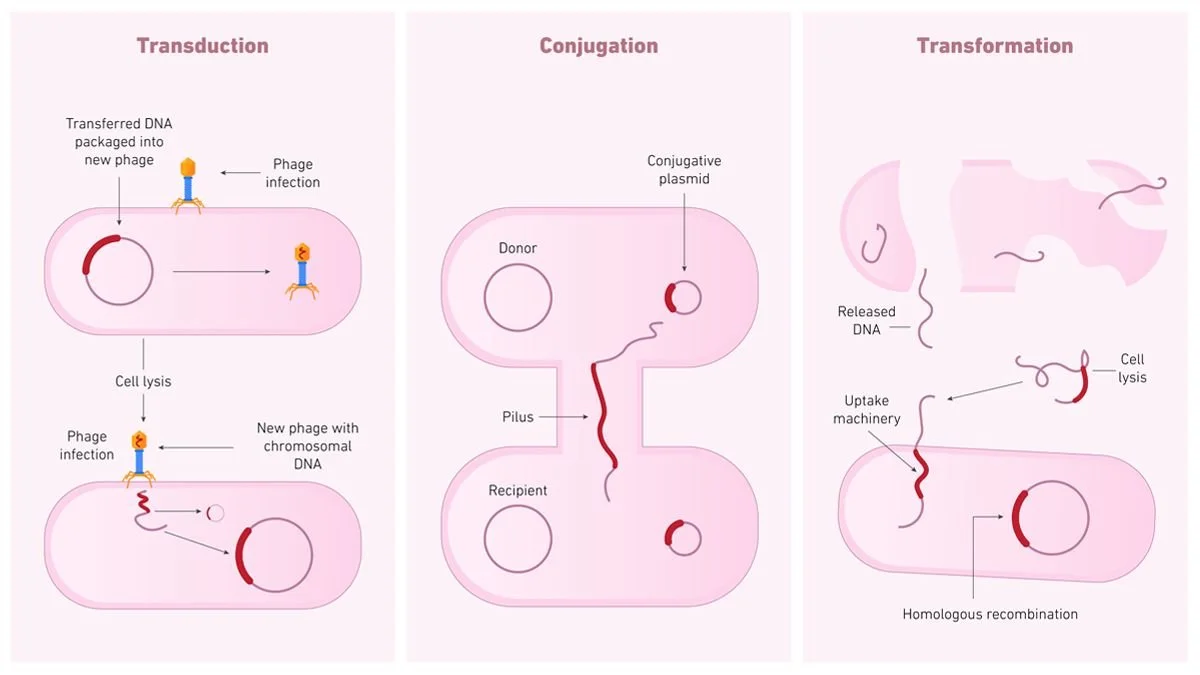

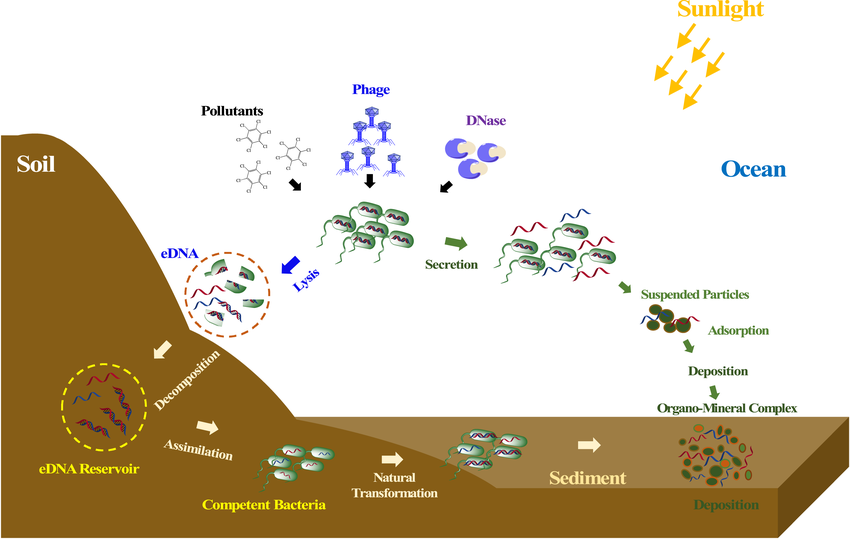

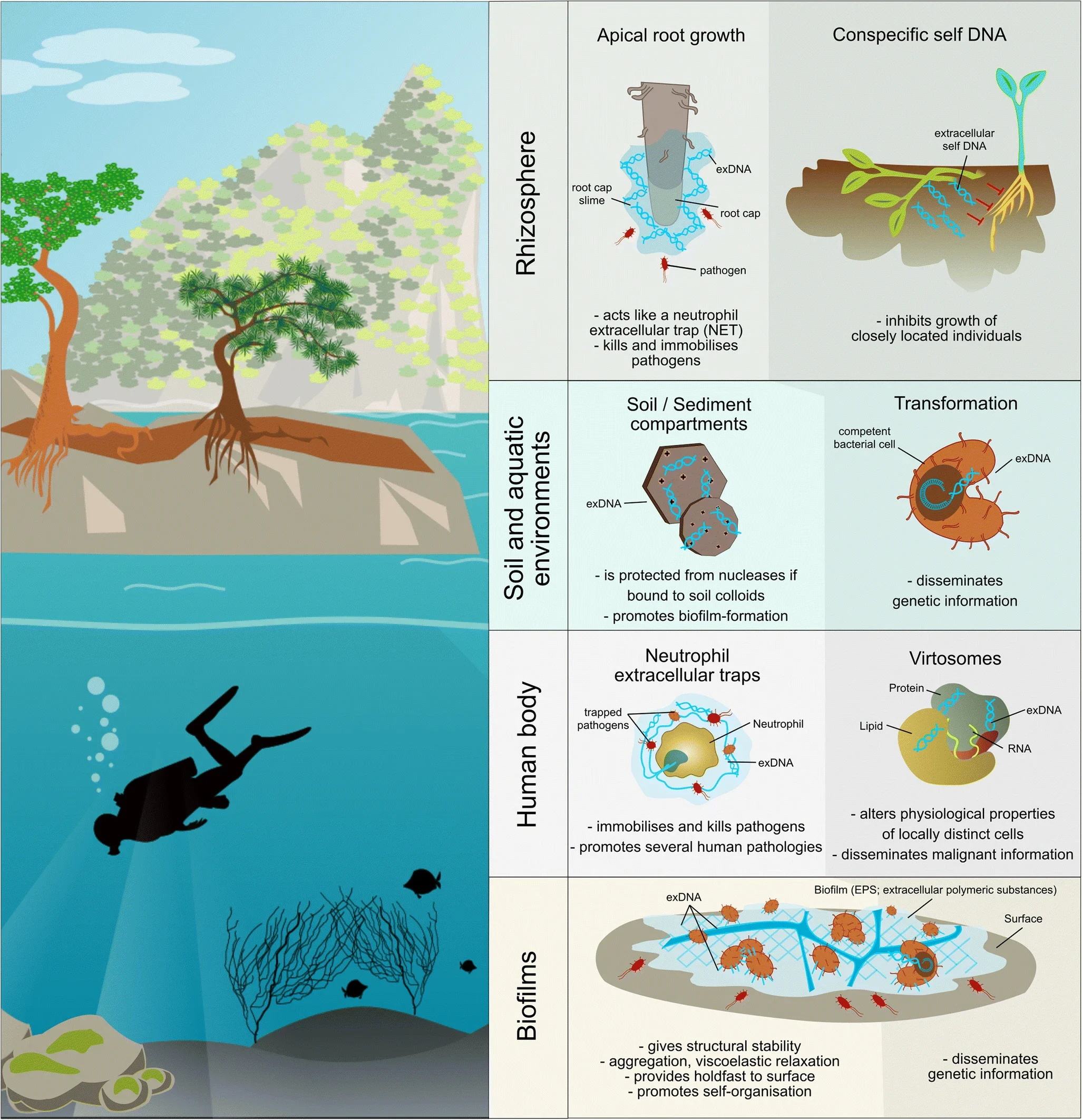

Transduction, a form of HGT, is mediated by bacteriophages, and in this process, the virus accidentally packages host bacterial DNA during its replication cycle and delivers it to a new bacterial cell upon infection. Conjugation, another method of HGT, involves the unidirectional transfer of mobile genetic material, such as plasmids and integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs), from a donor bacterial cell to a recipient bacterial cell via direct cell-to-cell contact mediated by a conjugative pilus and specific transfer machinery. Meanwhile, in transformation, competent bacteria actively take up free extracellular DNA from the environment and integrate it into their genome through homologous recombination or plasmid maintenance. Furthermore, while HGT is the leading provider of raw material for evolution and diversity in bacteria, this mechanism and the presence of relic DNA in the environment pose challenges for microbiologists and their attempts to study the bacterial realm, contributing to Bacterial Dark Matter, since constant gene swapping blurs species boundaries and might alter metabolic pathways potentially rendering some lineages unculturable, making assessment of microbial diversity far more complex than counting distinct lineages.

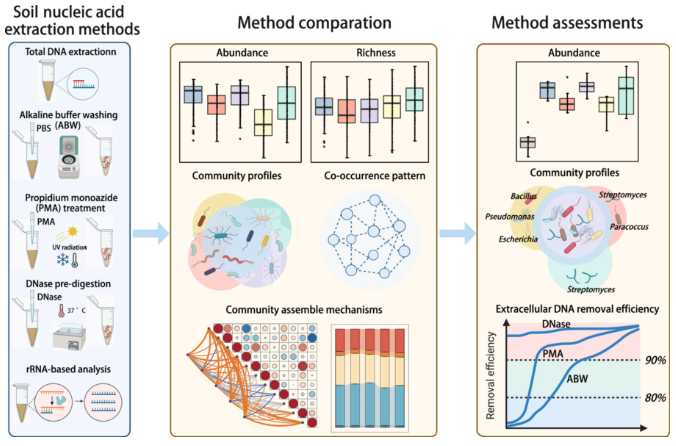

Relic DNA exerts a significant influence over the assessment of microbial diversity, particularly in soil environments, since it has been shown that around 40% of prokaryotic and fungal DNA in soil is either extracellular or originates from non-intact cells, confounding estimates of microbial richness and the relative abundance of different taxa, leading to an overestimation and a misleading picture of actual living microbial diversity and active community. Furthermore, HGT allows for rapid dissemination of genetic traits, including antibiotic resistance and virulence determinants, which can quickly alter the genetic composition of microbial communities at a faster rate than we can study them; since the high rates of gene uptake and loss via HGT result in a highly dynamic diversity within microbial communities where unrelated bacteria may share key genes, and closely related bacteria may differ drastically; while homologous recombination (HR) enables the exchange of genetic material between and within species, contributing to the fluidity of prokaryotic genomes, which can obscure clear taxonomic boundaries and thus challenge diversity assessments, making extremely difficult to capture a static representation of bacterial communities using traditional methods, making genomes patchworks of multiple evolutionary histories.

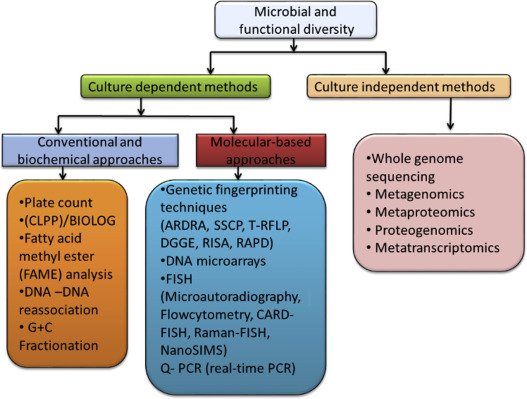

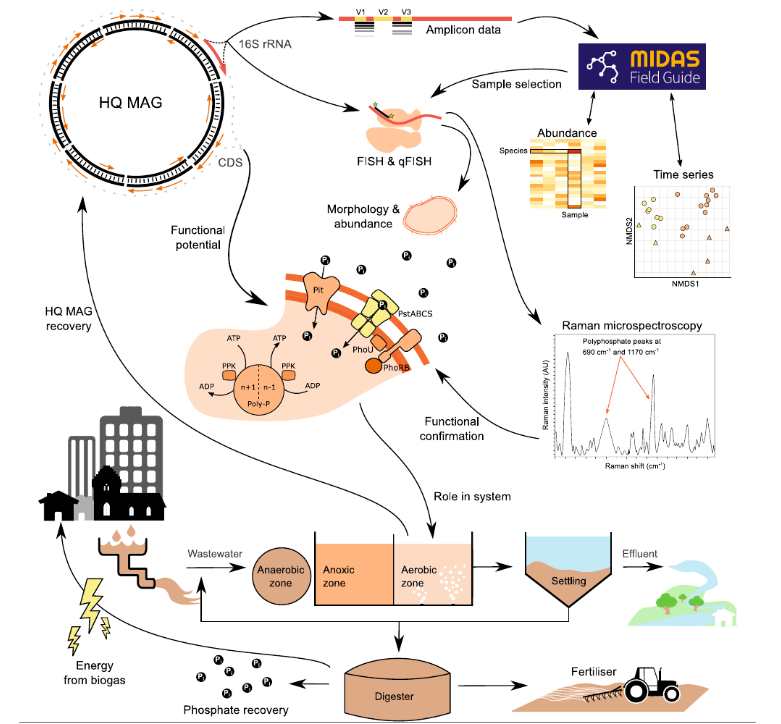

However, while HGT is an infinite source of genetic diversity that supplies Bacterial Dark Matter, microbiologists continually develop novel strategies and approaches to overcome the challenges posed by prokaryotic DNA exchange mechanisms and relic DNA when assessing microbial diversity. For example, reconstruction of nearly complete genomes directly from environmental samples is possible thanks to high-resolution metagenomics, since the recovery of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) has proven to be powerful for linking phylogenetic identity with functional potential, even for previously undescribed or unculturable organisms, with improved binning algorithms like MetaBAT, allowing the disentanglement of HGT from population structure by integrating long- and short-read sequencing.

Furthermore, microbiologists mitigate relic DNA noise by combining sequencing with DNase pretreatment, viability dyes, genome-resolved metagenomics, and community-level analyses of mobile genetic elements. Moreover, novel tools such as chromosome conformation capture and methylome analyses enable researchers to distinguish accessory gene pools from core genomes and to contextualize horizontal gene transfer as a community-level process rather than an analytical nuisance. Additionally, techniques designed to detect actively replicating microbial DNA and the rate of replication provide more accurate insights into the living, active members of a microbial community, overcoming the limitations of bulk DNA sequencing, which can include relic DNA. Overall, these novel strategies allow us, to some extent, to overcome HGT and relic DNA to elucidate Bacterial Dark Matter. Still, this is an arms race between the bacterial world and scientific methods that will never end, since intensive spatial sampling is necessary to identify temporal effects of HGT in microbial communities.

Referring to our opening quote, after filtering out confounding variables in our assessments of bacterial diversity, whatever remains must be the truth, and the truth is HGT and relic DNA will always be an infinite source of Bacterial Dark Matter.

What are your thoughts? Will we ever be able to catch up? Will we ever be able to fully sequence and classify all genetic material from environmental samples? Leave your comment below!

If you are interested in how relic DNA and HGT contribute to Bacterial Dark Matter, the links below are a great starting point for your research.